Fibromyalgia Basics

Closing Down Your Pain

One Trickle at a Time

Overwhelmed by the widespread pain of fibromyalgia? It would be so much easier if you only had a bum knee or sore ankle, then you could just tend to the one area. But even though your pain is everywhere, Roland Staud, M.D., and his team at the University of Florida in Gainesville, showed that focusing treatment on your most painful region will tone down your overall achiness. 1

In a prior study, Staud showed that the pain ratings of people with fibromyalgia were strongly dependent upon the pain intensity of their most troublesome areas.2 In particular, the regions that fibromyalgia patients said hurt the most were their shoulders, upper back, lower back, neck, and head. Trying to soothe the pain in these areas is a bit more manageable, but it’s still a handful. So why not take it one region at a time, starting with the source of your most intense pain?

Easing Shoulder Pain

… leads to greater rewards

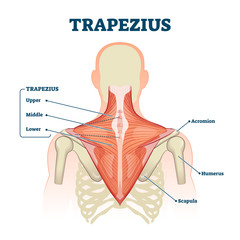

The two large triangular-shaped trapezius muscles, each extending from the base of your skull out to the tip of one shoulder and down to mid-back, are usually the greatest source of discomfort for people with fibromyalgia. In fact, these muscles are loaded with nodules that are the source of extreme pain called myofascial trigger points (MTPs). The trapezius muscles also happen to contain six of the 18 tender points that were once used to diagnose fibromyalgia.

Staud elected to relieve the pain caused by one MTP in the trapezius muscle to prove his theory that treating one area leads to a lowering of body-wide fibromyalgia discomfort. It’s based on the idea that the central nervous system in fibromyalgia patients thrives off incoming pain signals to keep it fired up. Each incoming “ouch” signal gets amplified and then redirected to multiple areas of the body to make a person hurt even more. So relieving pain in a small area of the trapezius muscle should lead to less central nervous system activity and less overall pain.

While this sounds logical, does it work? Can the enhanced pain sensitivity state in the central nervous system be tamed by eliminating the painful inputs from one muscle region? Staud’s goal was to prove this was the case – showing that targeted therapies designed to soothe particularly achy muscles (those with MTPs) are well worth the effort.

To knock out the pain in one area of the trapezius, Staud slowly infused lidocaine (an anesthetic) with a tiny needle into the muscle of fibromyalgia patients and healthy subjects. During another session at his clinic, he infused saline solution (used as a placebo). Neither the subjects nor the person who evaluated the subjects’ pain knew what they received.

Only a small amount of lidocaine was actually infused so that the drug’s effects were local and did not enter the blood circulation to cause systemic effects. In fact, a majority of the subjects were unable to guess correctly whether they receive an anesthetic or placebo. This is a good sign that the subjects remained blinded throughout both injection tests.

Before and after each infusion, the MTP area receiving the infusion was evaluated for the pressure pain threshold. This is the amount of pressure that the subjects detected as painful. There was no difference with the placebo, but after the lidocaine, the pressure pain threshold was significantly higher for both groups (fibromyalgia patients and healthy controls).

The most important test involved looking at the heat-pain threshold in the forearm on the same side as the shoulder infusion to show that easing the pain of one MTP in fibromyalgia patients could improve the pain at a location farther away. After the placebo, the forearm heat-pain threshold did not change in either of the two groups. However, after the lidocaine infusion, the fibromyalgia patient group showed a significant improvement in their forearm heat-pain threshold. No change was observed in the control group, which was expected because they do not have a central nervous system that amplifies muscle pain inputs.

Consider the Possibilities

Reducing the input from one MTP in a painful muscle increased the heat-pain threshold at a site farther away on the forearm. It was a “proof of concept” study, says Staud. “Tests using multiple local anesthetic injections into painful muscle areas may be required,” he says, to determine the potential ability of this procedure to treat overall fibromyalgia pain.

Staud points out that an anesthetic blockade of key painful areas in animal models with irritable bowel syndrome and complex regional pain syndrome returned the pain sensitivity back to normal. It’s as if by blocking the pain inputs to the central nervous system, that this system might revert back to operating normally again. This is promising because there are many overlapping features between fibromyalgia and these two conditions.

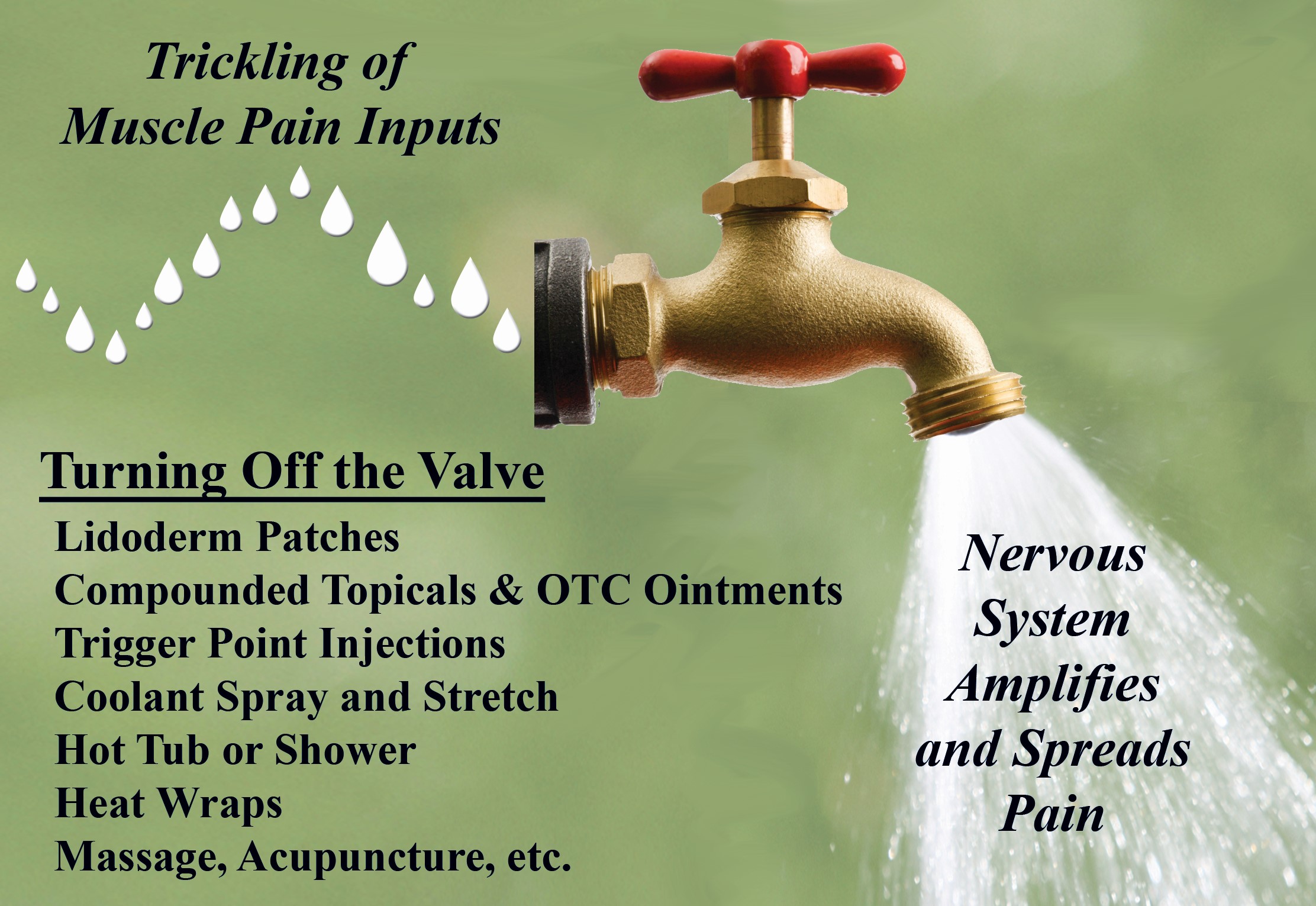

Would it be necessary to infuse massive amounts of anesthetics deep into your muscle tissues to get your central nervous system processes to start behaving more normally? Staud investigated this situation. Once an enhanced pain state has been reached in fibromyalgia patients, Staud found it only took a small trickle of stimulus input to keep the central nervous system pouring out amplified pain signals to multiple body regions. So at least in theory, reducing the muscle pain signals that are trickling in from your MTPs should have a significant impact on how you feel.

MTP Relief

Patch vs. Injection

Fibromyalgia patients usually have many MTPs that can be felt in tight, ropy muscles, and pressing on them shoots pain to other regions. In fact, MTPs may be a major source of muscle pain input that sustains the dysfunctional central nervous system.

There are many ways to relieve the discomfort of MTPs, such as massage, coolant spray with stretch techniques, and application of heat, but the most direct approach is needle insertion. The needle disrupts the process that causes the muscle fibers to be so tightly contracted, enabling the muscle to relax. A small acupuncture needle can be used, or a syringe. If the latter is employed, a small amount of lidocaine is injected into the area for pain relief.

Injections of an MTP with a syringe (not the tiny acupuncture needles) have two drawbacks: the syringe penetration makes the muscle very sore, and the procedure requires a skilled physician (not all doctors are trained in this area). In addition, the post-injection soreness tends to be more severe in fibromyalgia patients and the benefits may not be as great.3 So for people with fibromyalgia, an alternative treatment that doesn’t involve a needle and can be self-administered would be most desirable.

Acknowledging the disadvantages of MTP injections, a research team in Italy showed that an alternative approach to injections could also work. They used Lidoderm patches, which slowly release lidocaine into the tissues beneath.4

The study participants consisted of people with regional pain caused by an MTP (not fibromyalgia patients) who were divided into three treatment groups: injection therapy, Lidoderm patches, or placebo patches (Lidoderm look-alikes without the lidocaine). The Lidoderm/placebo sheets (2 3/4 x 2 inches) were cut into fourths and a new piece was placed on the MTP every 12 hours for four days.

At day five, 12 hours after the last patch was removed, subjects rated their pain at rest, on movement, function activity, and quality of life. No benefits were noted in the placebo group. The Lidoderm patch group showed a 75 percent reduction in these measures and the lidocaine injection group showed an 80 percent improvement. Four days later, the Lidoderm patch and injection groups continued to show benefits. Basically, there was little difference between the effectiveness of the Lidoderm patch and the MTP injection.

There was no discomfort caused by the patches. However, patients in the injection group still had post-injection soreness five days later. Also, at day nine (four days after the last patch was taken off), most of the subjects in the placebo group asked for a MTP injection while all of the patients who received the Lidoderm patches were satisfied with their treatment results.

This was a small study, but the authors suggest that Lidoderm patches might be an effective alternative for patients with MTPs who develop tremendous post-injection soreness. Most importantly, once the patches are prescribed by a physician, it gives a person with fibromyalgia more control over the pain that is feeding their central nervous system and causing an amplification of their overall achiness.

What does Staud think about the use of patches? “Lidoderm patches and injections work clinically for fibromyalgia patients. Prior to our project, no placebo-controlled study could detect more efficacy than placebo. Our study changed that.”

Hitting the Bullseye

Does it matter if the injection hits the center of the MTP? Will you still get pain relief if an area nearby your MTP is injected? No, the bullseye of the MTP must be injected in order for this form of therapy to provide relief for fibromyalgia patients. If your provider misses the target, then all you will get is post-injection soreness on top of your current level of pain.

To prove that MTP injection accuracy is essential, fibromyalgia patients were divided into two treatment groups: one that received an MTP injection with anesthetic and one that received an anesthetic injection nearby the MTP (the placebo group).5 Pain thresholds at the MTP site (located in the trapezius muscle), as well as several distant sites on the body, were assessed up to 30 days after the injections.

Patients who got their MTP injected (and thus, deactivated) demonstrated an increase in their pain threshold at the site of injection as well as in distant body regions. Their overall fibromyalgia pain was significantly improved, even up to a month after treatment of one MTP in the shoulder muscle. Pain thresholds did not improve in patients who received an injection that did not pierce the MTP. In fact, they all asked for and received a second injection (this time the real deal).

This study makes an important point: your practitioner must be a skilled “archer” or your body will become sore from target practice! If you “hire” a provider (physician or physical therapist who uses tiny needles) to deactivate your MTPs, they must be highly skilled at finding them. Otherwise, treatment attempts will fail.

1. Staud R, et al. PAIN 145(1-2):96-104, 2009.

2. Staud R, et al. Rheumatology 45:1409-1415, 2006. Article of Study Partly Funded by AFSA

3. Hong CZ, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 77:1161-66, 1996.

4. Affaitati G, et al. Clin Therapeutics 31:705-720, 2009.

5. Affaitati G, et al. Eur J Pain 15:61-9, 2011.

NOTE: See the section of Topical Ointments & Patches for more information about your lidocaine patch options.