Treatment & Research News

Is Fibro an Autoimmune Disease?

Could something in the blood be causing your fibromyalgia? Yes, says Andreas Goebel, M.D., Ph.D., of Liverpool, UK, along with his collaborators at King’s College London and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.* The researchers injected mice with serum from fibromyalgia patients and within two days the mice developed widespread pain. The immunoglobulin G (IgG) portion of the serum, which is loaded with antibodies, was found to be the pain-producing culprit. Serum without IgG had no impact.

Goebel suspects fibromyalgia may have an autoimmune basis and that autoreactive IgG might be responsible for the symptoms. But how could this occur in the absence of tissue damage that normally exists in autoimmune diseases? Goebel says the antibodies could be attacking the sensory nerves or nearby cells, which could increase the pain signals traveling to the spinal cord.

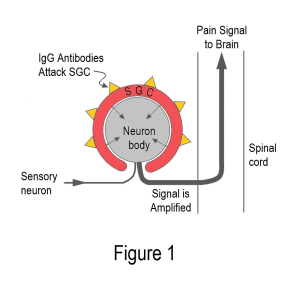

Examination of the serum-injected mice revealed IgG antibodies clustered around special immune cells called satellite glial cells or SGCs. As you can see from Figure 1, the SGCs surround the cell bodies of the sensory nerves. An attack on the SGCs can amplify sensory signals just before they enter the spinal cord. In addition, the chemicals secreted by the SGCs can enter the cerebral spinal fluid (which bathes the cord and brain) to cause more havoc.

Pain all over in the absence of obvious tissue destruction is a credibility nightmare for fibromyalgia patients. Yet, Goebel simply injected fibromyalgia serum into mice to cause pain, reduced activity (sign of fatigue?), sensitivity to cold, and reduced grip strength. Injecting serum from healthy subjects did not produce symptoms.

“Antibody-mediated immune processes in chronic primary pain (such as fibromyalgia) have been hiding in plain sight,” says Goebel. He adds that the antibody attack on the SGCs can’t be imaged, and standard lab tests cannot detect this process. Goebel’s findings also challenge the assumption that a person’s pain level corresponds to the degree of visible tissue destruction.

Injecting serum from patients into rodents to see if the symptoms can be reproduced is called a passive transfer study. It’s only been done in a few other diseases. Although the current project involved patients from two different centers, the findings still need to be replicated.

One last point: people are not mice. So how do the researchers know the SGCs are the cells under attack in humans? Goebel’s colleagues incubated the antibodies from fibromyalgia patients and healthy controls with SGCs taken from seven post-mortem subjects (none had fibromyalgia). Using a fluorescent dye and electron microscopy, the SGCs were heavily coated with antibodies from fibromyalgia patients. It’s as though the fibromyalgia antibodies are drawn to the SGCs like iron to a magnet.

Game Changer for Fibromyalgia

If Goebel’s work stands the test of time, fibromyalgia will be an autoantibody type of pain. This could be a game changer for fibromyalgia research because the condition is currently viewed as a dysfunctional central nervous system. Although plenty of evidence shows the brain and spinal cord do not operate properly, the cause remains unknown. However, if antibodies are attacking the SGCs, this could be the autoimmune trigger that causes the nervous system commotion.

Research points to multiple abnormalities in the central nervous system. The spinal cord contains too many pain messengers and not enough soothers. The pain control system doesn’t work, and the brain centers don’t provide a united front to contain the barrage of pain signals. Sleep is disrupted, hormones are dysregulated, and cognitive functions are diminished.

The foregoing findings are often packaged into the central sensitization theory to explain pain without a triggering source. It assumes that the central nervous system is hypersensitized to incoming sensory signals, but no one knows why. This, in turn, leads to an abnormally exaggerated response. In the case of fibromyalgia, a harmless trickle of nerve impulses might be transformed into widespread pain and other symptoms.

“Some say you don’t need a driving source to sustain central sensitization,” says Goebel, “but it has never been shown convincingly in any animal model. That’s why many of us (physicians and researchers) never really believed it.”

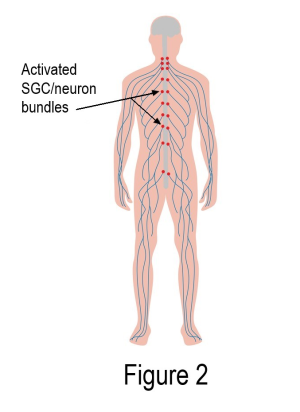

IgG autoreactive antibodies clustered around the SGCs may provide the missing piece to the fibromyalgia puzzle. As shown in Figure 2, activated SGCs form a pain-generating circuitry up and down both sides of the spinal cord (each red dot represents thousands of SGC/neuron units). Hurting from head to toe would be expected, not questioned! The spinal cord and brain would naturally be thrown into turmoil.

Study Implications

Wondering why your body is generating antibodies that attack the SGCs? Examining the mice won’t answer this question. “Our model takes it from the point where the IgG antibodies are already produced,” says Goebel. However, dissecting the tiny fraction of the IgG that is pathogenic (autoreactive) could lead to a disease marker. Goebel’s colleagues in Sweden are working on this.

What about treatments? As the IgG antibodies work their way out of the mouse’s body, the symptoms go away. So, approaches that dislodge the IgG antibodies from the SGCs should work, even if they do not stop the antibody production.

Currently, therapies in this category are extremely expensive and not yet available to fibromyalgia patients. However, a small “proof-of-concept” type of trial is underway to test an intravenous drug called rozanolixizumab.

Alternatively, tempering the SGC activation that leads to amplification of the sensory signals might work to reduce fibromyalgia symptoms. For example, low dose naltrexone targets specific receptors on the SGCs to quiet them down. This approach could never be as effective as removing the harmful antibodies from the SGCs, but it’s available and cheap.

Presuming autoantibodies to your SGCs are driving your symptoms, this may explain why medications that work in the spinal cord produce dismal results. Examples include the three FDA-approved drugs (pregabalin, duloxetine, and Savella) that operate downstream of the SGCs. Using them could be the equivalent to putting a bucket under a leaky faucet, while targeting the SGCs would be more akin to repairing the faucet.

Bottom Line

Once Goebel’s work is replicated and the word spreads about the passive transfer study, fibromyalgia will gain more credibility. And using Goebel’s mouse model will help researchers identify the mechanisms responsible for fibromyalgia and develop effective treatments. It could be a long road ahead, but at least research will be moving in the right direction.

* Goebel A, Krock E, Gentry C, et al., 2021. Passive transfer of fibromyalgia symptoms from patients to mice. J Clin Invest. 131(13):e144201.