Projects Funded

Tender Points are Mostly MTPs

Tender points are the pain areas initially used to diagnose fibromyalgia. Doctors abandoned the tender point exam in 2016 for the survey-driven criteria, but these sensitive areas hold tremendous significance. Studies by Hong-You Ge, M.D., Ph.D., and Cesar Fernandez-de-las-Penas, Ph.D., show 90 percent of fibromyalgia tender points are myofascial trigger points or MTPs. In addition, both researchers found that MTPs substantially contribute to your overall pain. Study highlights along with a strategy for treating MTPs to reduce your body-wide pain are below.

Fibromyalgia

The Mirror Image of Normal?

You hear it all the time, you look just fine. Even when the doctor conducts an exam and standard tests, nothing shouts out that you have pain all over. So why are your muscles tender to the touch? What could be going on beneath the surface that is causing you so much grief but leaves you looking normal?

Perhaps a physical therapist told you that some of your muscles feel ropy and your range of motion is poor. Or maybe your massage therapist can zero in on your fibromyalgia pain points, like a marksman at target practice. Are these hands-on specialists detecting something that others fail to notice? Yes.

The studies by both researchers identify a very fine distinction in the muscles between healthy pain-free people and fibromyalgia patients. It has to do with myofascial trigger points (MTPs), the areas that hurt and radiate pain elsewhere in fibromyalgia patients. But the explanation is not what you might think. Ironically, most everyone has MTPs—even people who don’t have pain—but yours are slightly different.

Turned On

The presence of MTPs in your achy muscles doesn’t distinguish you from healthy people, according to Hong-You Ge, M.D., Ph.D., of Denmark. He found 11 MTPs (on average) in a group of fibromyalgia patients and a similar number in pain-free controls.1 Ge also discovered that the MTPs tended to occur more commonly in the same areas of the musculature. Interestingly, he found one very important difference: the state of the MTPs.

Your MTPs are turned on (they are active), while everyone else’s are in a dormant state (they are latent). You could be trying to relax, and your active MTPs will be causing you pain. No one needs to press on your active MTPs for them to hurt. In healthy people (pain-free), their latent MTPs are not turned on, so they don’t produce any discomfort.

“The large number of latent MTPs in the healthy volunteers for our study was surprising, but true,” says Ge. What could these tiny, difficult-to-find nodules in the muscles be doing if they don’t produce noticeable symptoms? “These latent MTPs may serve as a potential source of pain and fatigue in healthy subjects following acute and sustained muscle overload, trauma, or other adverse events.”

Does this mean that multiple latent MTPs in people are lying in wait, ready to be turned on to cause fibromyalgia? Not quite. Ge says that MTPs must be chronically activated for a long time to become the active pain points in fibromyalgia. In other words, latents are generally “silent” in everyone. When activated by daily movements that strain the muscle, they will cause temporary discomfort but then revert to latents. These daily processes do not lead to the widespread muscle aches of fibromyalgia.

Reflections of Pain

If latent MTPs don’t cause pain, how did Ge locate them in healthy people in the first place? He mapped the active MTP locations he found on the fibromyalgia patients onto healthy height-weight-matched controls. It’s somewhat like reflections in a mirror, which enabled Ge to examine these regions for the painless nodules known as latent MTPs.

For starters, the 30 fibromyalgia patients shaded in their pain locations onto the front and back sides of a body drawing. Based on each person’s pain drawing, an examiner palpated the shaded areas for the presence of active MTPs. These areas feel like little knots in a tight muscle band. In addition, pressing on them causes a magnification of the pain that also radiates to other areas.

Ge didn’t use the diagnostic tender points to identify the active trigger points in the fibromyalgia patients. Instead, he let the fibromyalgia patients’ pain drawings guide his search for MTPs.2 This method allowed Ge to identify the most likely areas for active MTPs in people with fibromyalgia.

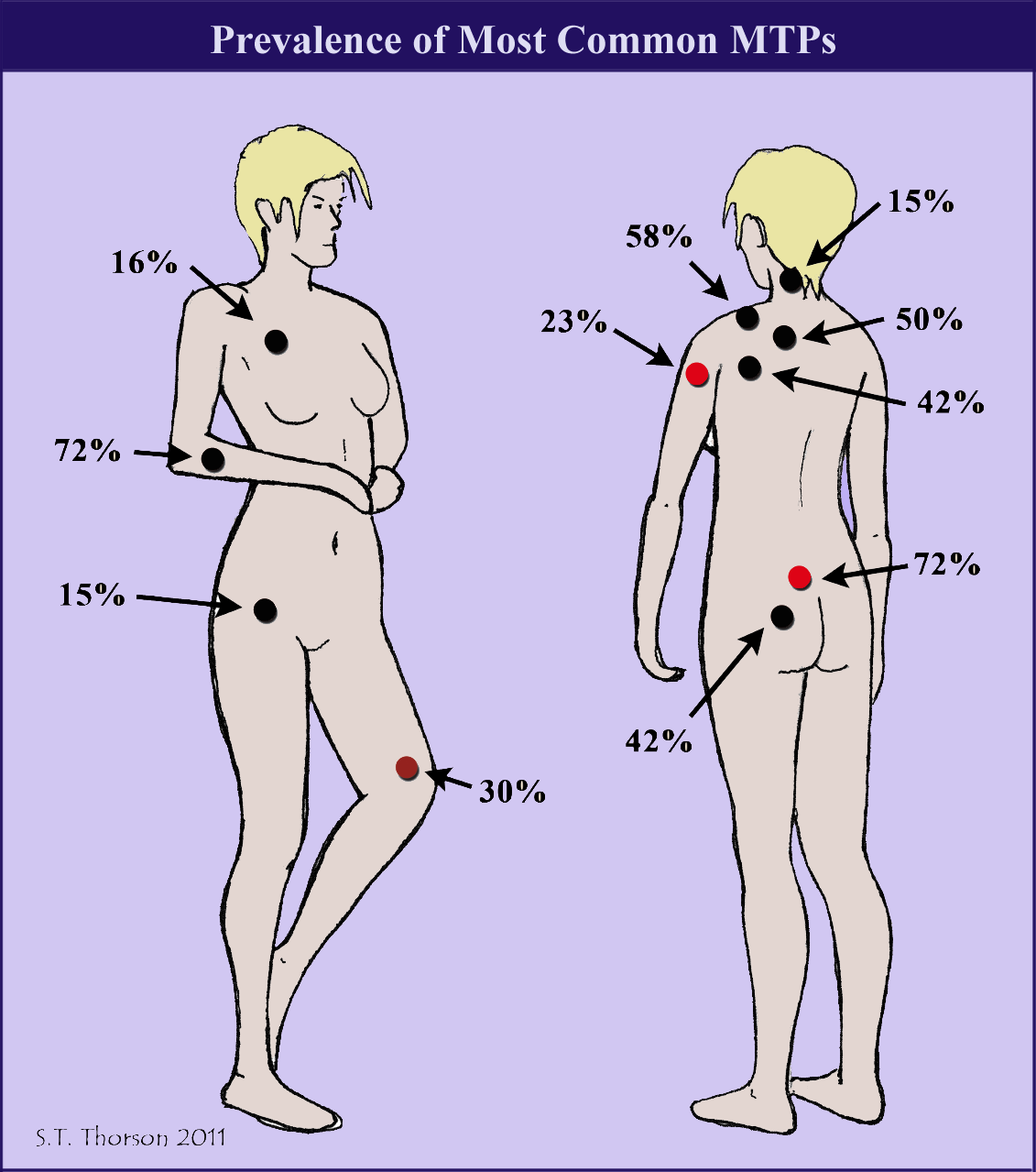

Forty areas for potential MTPs, 20 on each side in a symmetrical pattern, were identified by the fibromyalgia patients. On average, each fibromyalgia patient had 11 active MTPs. The most common locations are shown on the mannequins in the drawing.

When Ge examined the control subjects, he did not find any active MTPs, only 11 latents. This was no surprise because the healthy subjects did not have pain. Yet, Ge still identified an average of 11 latent (not active) MTPs per healthy subject. In addition, the latent locations mirrored what Ge found for the active MTPs in the fibromyalgia group.

So, the difference between you and healthy folks is that your MTPs are turned on (active) and theirs are latent. For the distinction, read What’s Driving Your Pain?

Symmetry

The number of key active MTPs on the right side of the body for fibromyalgia patients appears to match those found on the left side. Why the symmetry?

“This is likely due to dual activation of the muscle groups for performing most physical activities,” Ge says. Or it could be caused by the spreading of pain from one side of the spinal cord to the other. Either way, this is an important clue when identifying and treating active MTPs in people with fibromyalgia.” For example, if an active MTP exists in your right forearm below the elbow, check the other arm!

More Active MTPs

Greater Pain

The greater number of active trigger points, the greater the pain severity in people with fibromyalgia. Both Ge and Cesar Fernandez-de-las-Penas, P.T., Ph.D., of Spain, identified the correlation between MTPs and pain.3 So, if you have more active MTPs, your fibromyalgia pain will be worse. In addition, your sensitivity to painful stimuli is also increased by a greater number of active MTPs.

Fernandez-de-las-Penas examined a group of 45 fibromyalgia patients along with the same number of control subjects. He found that “the higher the number of active MTPs, the lower the pressure pain threshold levels.” The pressure pain thresholds were assessed at multiple regions on the body (not over the MTPs). As a result, his findings reflect a generalized enhancement of your body’s ability to detect pain. Researchers call this a reduced pain threshold.

Like Ge, Fernandez-de-las-Penas found an average of 10 active MTPs in his fibromyalgia group. On the other hand, he only detected latents in the healthy subjects.

Fibromyalgia Reproduction

How much of your fibromyalgia pain is caused by your active trigger points? Both Ge and Fernandez-de-las-Penas addressed this question. Each time they pressed on an active MTP, patients shaded the areas that hurt on a body diagram. A composite pain drawing representing all the active MTPs was generated for each patient. The same was done for the latent MTPs in the healthy group, which only produced a negligible amount of discomfort.

“The local and referred pain elicited from widespread active MTPs fully reproduced the overall spontaneous fibromyalgia pain pattern,” says Fernandez-de-las-Penas. Ge’s research produced the same results. In other words, your tender areas or active trigger points are responsible for generating your body-wide fibromyalgia pain pattern. However, your pain intensity is not uniform throughout your body.

“Looking at the patient’s pain drawings,” says Ge, “it is easy to understand that the pain of fibromyalgia is not necessarily diffuse throughout all areas of the body. Rather, it consists of regional pains that are most concentrated in the neck, shoulders, arms, low back, and gluteal/hip regions. These areas likely correspond to regions of the body where the muscles are more prone to becoming over-used or over-strained.”

Treatment Approach

Unlike the 18 diagnostic tender points for fibromyalgia, identifying trigger points (or MTPs) improves treatment success. “Most fibromyalgia patients have key active MTPs in other muscle areas besides those previously used for diagnosis,” says Ge. “If these active MTPs in other muscles are not treated, fibromyalgia pain will persist.” Ge suggests that “pain drawings provide a great aid for locating key active MTPs.”

Pain drawings identify your most intense regions of pain. Then these drawings can serve as a tool to help your provider prioritize which areas to treat first. However, an understanding of the referred pain patterns produced by MTPs is essential. For example, Ge comments that an MTP in a back shoulder muscle will likely shoot pain to the front of the shoulder. So, while your pain drawings form the basis for your individualized care, you need a provider to interpret them. In other words, someone who understands how MTPs refer pain to other muscle groups.

Physical therapists and deep-tissue massage experts often possess the talent needed for treating your painful MTPs. Some physicians, particularly physical medicine specialists or physiatrists, are also skilled at pinpointing MTPs and applying techniques to alleviate the discomfort that they produce. David Simons, M.D., and Janet Travell, M.D., published a two-volume manual illustrating the location of all known MTPs.4 If your provider is not familiar with these two famous physicians, ask for a hands-on specialist who is.

Although the tender point exam is not used for diagnosing fibromyalgia, identifying trigger points is an essential step in treatment. Research shows that deactivating just one active MTP leads to an increase in pain thresholds in fibromyalgia patients. Just think of the benefits you can reap by treating several of your active MTPs? See our articles, Closing Down Your Pain and Identifying & Treating MTPs for advice.

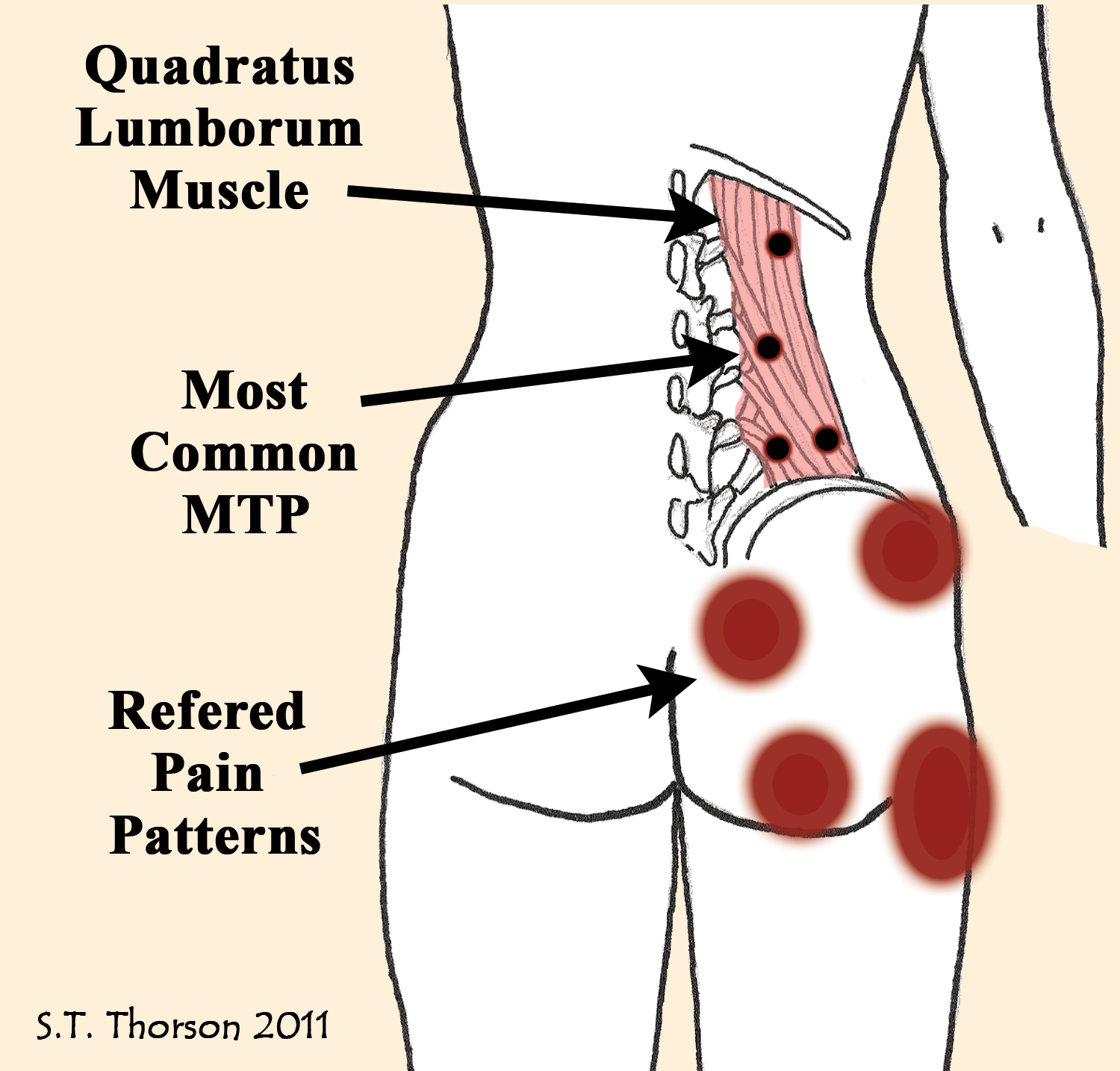

Spotlight on Back Pain

The quadratus lumborum attaches at the back ridge of your pelvic bone and fans out into multiple sections, each one attaching to a different level of the vertebrae in your low back or lumbar region. Surprisingly, this muscle was never part of the tender point exam for fibromyalgia. Yet, Ge confirms that MTPs in this muscle are the most common cause of low back pain and referred pain to the hips and gluteal muscles (e.g., buttocks).

What are some of the signs that your quadratus lumborum might have an active MTP? Turning over in bed, standing upright, bending over to lift objects, or twisting the trunk are movements that aggravate this MTP to produce more pain in the muscle.4 Getting out of a chair can also be agonizing if the quadratus lumborum contains an active MTP.

Stay current on Treatment & Research News: Sign up for a FREE Membership today!

For more info on MTPs and treatment methods, see our section on Muscle Pain Relief.

Symptoms | Medications | Alternative Therapies | Finding A Fibro Doctor | Exercise Difficulties

Fibromyalgia Tender and Trigger Point References

- Ge HY, et al. Arthritis Res Ther 13(2):R48, Mar 22, 2011. Free Journal Report

- Ge HY, et al. J Pain 11(7):644-51, 2010. Free Journal Report

- Alonso-Blanco C, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, et al. Clin J Pain 27(5):405-13, 2011. Abstract

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Pain Manual; Vol. 2., The Lower Extremities, Lippincott Wiliams & Wilkins, 1992.

AFSA’s funding to Dr. Ge produced four research papers and other studies looking at how MTPs cause muscle pain and fatigue. A summary of these two papers (reference 1 and 2) is provided below. In addition, AFSA’s funding to Dr. Fernandez-de-las-Penas (reference 3) was the initial project that led to his many other studies on fibromyalgia.

The journal reference documenting the high prevalence of MTPs in the trapezius muscle of fibromyalgia patients is below. It was also part of the AFSA-funded study to Dr. Ge and the results are described in the article: What’s Driving Your Pain?

Ge HY, et al. Contribution of the local and referred pain from active myofascial trigger points in fibromyalgia syndrome. PAIN 147(1-3);233-40, 2009. Abstract

Another report by Ge shows that a fatiguing muscle contraction of the trapezius occurs more rapidly in fibromyalgia patients due to MTPs. In addition, the MTPs give off electrical activity, sending signals into the central nervous system and causing reduced pain threshold in a distant leg muscle. This study explains why exercising one muscle leads to more pain in other muscles in the body. It was also part of the AFSA-funded study to Dr. Ge and is described in the article: Managing Fibromyalgia Pain.

Ge HY, et al. Descending pain modulation and its interaction with peripheral sensitization following sustained isometric muscle contraction in fibromyalgia. Eur J Pain 16(2):196-203, 2012. Abstract